“Your education today is your economy tomorrow,” is a quote from Andreas Schleicher from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), who has become one of the world’s most influential figures in education. I took this statement off the PISA Day website. In the view of Mr. Schleicher, a nation’s economy hinges on education (performance). Although there is data to refute this, organizations such OECD, make the claim that your student’s performance on school tests will have a major impact on the nation’s economy. A nation’s economy and it’s ability to compete is much more complicated than laying the blame on its students and teachers. And one’s ability to “compete in the 21st century” is also more complicated than one’s report card.

Results as reported by PISA helps shape the public image of science education (or mathematics education), and it is unfortunate that educators allow this to happen. Dr. Svein Sjøberg of the University of Oslo in a publication entitled Pisa and Real Life Challenges: Mission Impossible, questions the use of tests such as PISA. He informs us that:

The PISA project sets the educational agenda internationally as well as within the participating countries. PISA results and advice are often considered as objective and value- free scientific truths, while they are, in fact embedded in the overall political and economic aims and priorities of the OECD. Through media coverage PISA results create the public perception of the quality of a country’s overall school system. The lack of critical voices from academics as well as from media gives authority to the images that are presented.

PISA measures only three areas of the curriculum (math, science, reading), according to Dr. Sjøberg , and the implication is that these are the most important areas, and areas such as history, geography, social science, ethics, foreign language, practical skills, arts and aesthetics are not as important to the goals of PISA. The other international test, TIMSS, according to his analysis (and I would agree) is based on a science curriculum that many science educators want to replace, yet uses test items that could have been written 50 years ago. In general the public is convinced that these international tests are valid ways of measuring learning, and that the results can be used to draw significant conclusions about the effectiveness of teaching and learning.

If you live in the world of psychometrics and modeling, the results that are gathered by these international testing bodies is a dream come true. Sjøberg puts it this way:

PISA is dominated and driven by psychometric concerns, and much less by educational. The data that emerge from these studies provides a fantastic pool of social and educational data, collected under strictly controlled conditions – a playground for psychometricians and their models. In fact, the rather complicated statistical design of the studies decreases the intelligibility of the studies. It is, even for experts, rather difficult to understand the statistical and sampling procedures, the rationale and the models that underlie the emergence of even test scores. In practice, one has to take the results at face value and on trust, given that some of our best statisticians are involved. But the advanced statistics certainly reduce the transparency of the study and hinder publicly informed debate.

PISA Day 2013

It’s PISA Day, and now everyone knows who is at the top and the bottom of the “leader Board.”

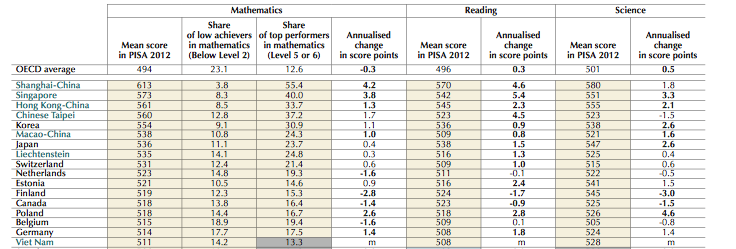

PISA League Table showing the top dozen or so nations on the 2013 PISA international assessment of 15 year-olds. League Tables like this one create PISA envy. But the data also is manipulated to create fear which is good for those who benefit from constant reform of education, especially in the U.S.

On English TV, league tables are used to report the PISA results, with little else mentioned. The UK is falling behind, again, says one TV reporter. The whole enterprise is summed as a global race (to the top), and nations such as the UK and the US scored lower in the League Tables.

In England the argument becomes a political one, in that the present government puts the blame on the regime that was in power a decade ago.

Interestingly, the reports highlighted factors that seem to be characteristic of nations that fared well on the tests: teacher autonomy and decision-making power; emphasis on localized curriculum development; and emphasis on problem solving and not high-stakes testing.

These characteristics are absent in the UK and US education system. Each country has moved to an authoritarian standards-based and high-stakes testing. Teachers are removed from the decision-making process, and more and more, it’s the opinions of policy makers such as politicians, corporations, and private foundations run by a few very wealthy people.

The PISA assessments have gathered enormous amounts of data thanks to the cooperation of more than 510,000 15 year olds from nearly 70 countries.

Whose Happy in School?

One interesting aspect of the PISA assessment program was students’ perception of school. They were asked if they were happy at school? The results, by and large, showed that in nations where students did not perform at the highest level academically, the students reported a higher “happiness” score than the nations whose students were at the top of the League Standings. Students who were happiest at school included Indonesia, Albania, Peru, Thailand, and Columbia. The least happy students were in Korea, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Estonia, and Finland. Note: the U.S. was in the bottom third of the happiness scale, while the UK was half way up the scale.

Snapshots of Data

More to come, in the meantime:

Follow this link to see snapshots of the data collected by PISA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.