For the past 13 years, American schools have endured a rebirth of an “industrial culture” that is the product of “mechanistic age thinking,” described in-depth by Russell L. Ackoff (public library) in his writings, speeches, interviews and courses. This rebirth has been waved over us by reformers whose self-interests, wealth, and corporate networks have resulted in a movement to privatize, and standardize education in the context of the American democracy.

I am going to argue here that instead of this industrial culture, teachers and students need to the freedom to teach and learn. Nothing less is acceptable.

For most of my adult life, I have been involved in humanistic psychology and education, and have promoted holistic and experiential learning, especially in science, and science education. My development in this attempt has been influenced by many people, including theorists, scientists, close colleagues and fiends, fellow teacher educators, and especially practitioners in classrooms around the U.S., Russia and Spain.

Freedom to Learn

The freedom to learn is not only a philosophy of life, but it is a theoretical idea that can be applied to professional teaching K-college. When a child is born, her parents do what they can to offer an environment for exploration, discovery, and play. In this context, parents are creating an environment where the child has the freedom to learn. This idea should be at the heart of teaching at any level–from pre-school education to advanced graduate work.

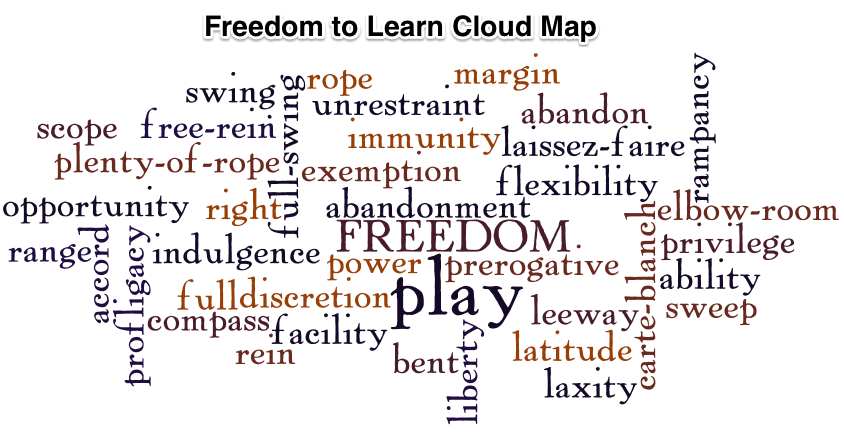

Figure 1. The synonyms of the word freedom appearing from a search on thesaurus.com. Wordle, © 2013 Jonathan Feinberg

Acting on the philosophy of freedom to learn does not lead to a classroom of disorder, chaos, abandon or laissez-faire. Freedom to learn has many interpretations and applications. The word cloud that is shown in Figure 1 is word cloud of a search the word “freedom” on thesaurus.com.

Many of these words characterize classrooms where teachers are working cooperatively with students to create an environment in which students are participants in some or all aspects of the course, program or grade level. Which of these words would you select to describe your approach to teaching? What words would you add to this cloud map?

For example, in an introductory college geology course, I worked with students individually to name the content, concepts and laboratory activities they would pursue in a one-semester geology course. If two or more students choose similar topics, they would team up and work out a plan of investigation. In all cases, students would be involved in teaching the rest of the class what they were studying and what they were learning.

In courses in humanistic education/psychology, several sessions were held among the instructor and students to cooperatively create the syllabus, activities, and assignments for the course. In other courses, (actually all of my courses) no tests were given. Students, instead either wrote a contract outlining their aims and how they would meet them. In other cases, students would keep an elaborate portfolio of their work, which would be evaluated by a team of instructors, followed by an interview with the student and instructors.

For my professional work as a teacher, freedom to learn meant cooperation among students and instructors. We learned together. In most courses, students could read what ever they wanted to read, and were simply asked to comment on what they got out of the reading. Team learning was at the heart of learning in these courses. It didn’t matter if it was an introductory science course, a course in pedagogy, curriculum, or research. All them were organized as team learning experiences.

I carried this model with me to the Bureau of Education and Research (BER), and from 1990 – 2003, I conducted hundreds of seminars for middle and high school science teachers (normally 50 – 150 teachers in a seminar). At each seminar, teachers worked in teams, and explored the content of the seminar (science teaching strategies, cooperative learning, Internet-based teaching) experientially. There was little to no lecturing, instead students engaged in professional dialogue and discussions brought about through a series of collaborative activities and investigations.

While I was a graduate student at The Ohio State University in the 1960s (yup, that’s right), my advisor, Dr. John Richardson, suggested that I read Carl Rogers’ book, On Becoming a Person (public library). You can read between the lines, but I think he had something in mind for me. But later in my life, when I read what others have written about this book by Rogers–that it was revolutionary thinking–did I realize how significant Richardson’s recommendation was for me.

In 1969, the year that I finished my Ph.D. at Ohio State, Rogers published Freedom to Learn (public library), the most important book published to date on humanistic education. The book became the guide that I used as a professor of science education at Georgia State University, where I worked from 1969-2003. It was a guide in the sense that it encouraged me to be experimental with my courses, and the programs that I developed, and working with others at GSU, had the gumption to swim upstream away from more traditional approaches to teaching and especially, teacher education.

Carl Rogers, in his book, Freedom to Learn, shifted the focus from to teaching to learning. In fact in this groundbreaking book, he confessed that anything that can be taught to another is relatively inconsequential, and has little or no significant influence on behavior. He wrote that “this sounds so ridiculous I can’t help but question it at the same time that I present it.”

Anything that can be taught to another is relatively inconsequential…Rogers, Carl, 1969, Freedom to Learn

Rogers shift in thinking was a critical transformation in his own views about teaching and learning. To him the purpose of teaching is to facilitate the learning of students. His view, which is quoted below, is a personal one, yet at the same time it is powerful in exposing the virtues of learning. Here is what he said:

I realize increasingly that I can only interested in learnings which significantly influence behavior. Quite possibly this is simply a personal idiosyncrasy.

I have come to feel that the only learning which significantly influences behavior is self-discovered, self-appropriated learning.

Such self-discovered learning, truth that has been personally appropriated and assimilated in experience, cannot be directly communicated to another.

The Rogerian principle, “Self-discovered learning cannot be directly communicated to another” is in direct conflict with the reform agenda that has grasped nearly every school in America. When you really listen to these so-called reformers, especially the words of Bill Gates, they believe that students either absorb content “given out by the teacher,” or their brains are simply receptacles which are filled up (or not) by teachers. And of course, they put the nail in coffin by narrowly defining and measuring how much the cup is filled by giving a multiple choice test which may or may not be related to the content and curriculum the students experienced.

All Together

There are some ideas that I’d like to explore here that I hope will amplify my belief that all students, at any level, should be given the freedom to learn. I’ll start with the writing of Fritjof Capra, a theoretical physicist who has written ground breaking books including The Tao of Physics (public library), The Turning Point (public library) , The Web of Life (public library), and The Hidden Connections (public library).

My reason for starting here is that Capra’s views are holistic and systemic which is fundamental if we are to truly reform education. Capra’s ideas, which he developed over a period of decades using a form of research which relies on dialogs and discussions with people and small groups of colleagues. His ideas are important and what follows is a brief discussion of some of his ideas and how they might be applied to learning.

In 1975, Capra wrote the groundbreaking book entitled The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism (public library). In Capra’s view, the natural world is one of “infinite varieties and complexities; a multidimensional world which has no straight lines or completely regular shapes, where things do not happen in sequences, but all together.” Capra viewed the Eastern philosophy as a new paradigm, one that was holistic and integrated, and not a dissociated collection of parts.

It is this essential idea that forms for me the starting place to discuss learning. Learning is holistic and integrated, and for learning to happen, students must have the freedom to learn. For this to happen, cooperation needs to assert itself as an important aspect of establishing a teaching and learning environment. An idea that follows here is that teachers could work with students to help them choose what, when and how students learn. As radical as it might sound, I’ll explore this idea with theoretical, experiential, and personal data.

When we design school for learning (instead of teaching), principles drawn from our understanding of nature will go a long way in giving us clues and directions. In this regards, Capra made this statement in his book The Hidden Connections (public library):

The design principles of our future social institutions must be consistent with the principles of organization that nature has evolved to sustain the web of life. A unified conceptual framework for the understanding of material and social structures will be essential for this task. Capra, F. 2002. The Hidden Connections: Integrating the Biological, Cognitive, and Social Dimensions of Life into a Science of Sustainability.

As teachers we should consider applying Capra’s framework to the structures of learning and teaching that we experience as professional teachers, whether it be pre-school, or graduate school. Learning is a web–an interconnection of ideas, people, events, experiences, attitudes, opinions….

Capra suggests an intriguing idea in his latest book. What would have happened if Leonardo’s ideas were the basis for 19th and 20th century science?

Capra, in The Science of Leonardo (public library), argues that the true founder of Western science was Leonardo (1452-1519), not Galileo (1564-1642). However, it was the science of Galileo that influenced later scientists (Newton, 1643-1727) who stood on Galileo’s shoulders.

Capra, in The Science of Leonardo (public library), argues that the true founder of Western science was Leonardo (1452-1519), not Galileo (1564-1642). However, it was the science of Galileo that influenced later scientists (Newton, 1643-1727) who stood on Galileo’s shoulders.

Capra wonders what would have happened if these 16th – 18th century scientists had discovered Leonardo’s manuscripts, which were “gathering dust in ancient European libraries. You see, Capra shows that Leonardo’s view was a synthesis of art and science, and indeed science was alive, and indeed science was “whole.” Leonardo was ahead of his time in understanding life: he conceived life in terms of metabolic processes and their patterns or organization.

Capra suggests that Leonardo, instead of being simply an analytic thinker, was actually a systemic thinker preceding the lineage established by scientists and philosophers including Wolfgang von Goethe, Georges Cuvier, Charles Darwin, and Vladimir Vernadsky. Would it be fair to suggest that Capra’s uncovering of Leonardo’s holistic view of science a rationale to critique the Next Generation of Science Standards which have divided science into its traditional offerings, and further broken each science into bite sized student performance? Just a thought.

Needless to say, thinking in wholes has an immediate application to learning. Instead of the industrial model of breaking content into behavioral sentences (behavioral objectives!), student performances, or to be on the side of the industrial reformists, core standards in math, science, and language arts, we need to reject these ideas, and argue for a transformation that focuses on learning, learning how to learn, giving students the freedom to learn.

Freedom to Think in Wholes

Fritjof Capra’s research has led to a greater understanding of systemic and complex systems, including learning and schooling. His contentions are a social system (such as a classroom or a school) is a self-generation network of communications. According to Capra, we can’t direct a social system, only disturb it. Our creativity and adaptability arises at critical points of instability of the system. Leadership (a teacher in a classroom, or the principal of a school) is really the facilitation of a learning culture in which questioning and innovation are encouraged.

Thinking in wholes, networking, webs, interconnections, or systems opens a different kind of world for us, especially in the teaching and learning profession. In his new book, The Systems Thinking School (public library) Peter A. Barnard states that systems thinking seeks interconnectivity. His book is a powerful thesis on how systems thinking can be applied to schooling. Although his book is for the transformation of schools, it can also be applied to the transformation of the classroom.

In this next quote from Barnard, he talks about the school as a system. Read the quote, substituting schools with classrooms, and step back and take a look at our own places of work. If we think of the classroom as a system, and face many of the assumptions that have restricted us, what possibilities do you see?

Schools have to somehow see and come to terms with the idea that not all is as it seems and that many assumptions about learning and school systems management no longer work but remain endemic to our thinking. To confront the system that a school operates for the basket case it is, with all its illusory fixes and reforms, means exposing assumptions and looking again at the underpinning management knowledge base. In effect, schools have to unlearn the false rationale of separatist, component, tool-box thinking if they are to prevent old ideas and assumptions from hitching a ride with them on the road to school improvement. Barnard, Peter A. (2013-09-19). The Systems Thinking School: Redesigning Schools from the Inside-Out (Leading Systemic School Improvement) (Kindle Locations 368-372). R&L Education. Kindle Edition.

What is your view of learning? To what extent do think it is possible to give students the freedom to learn?

You must be logged in to post a comment.