P.L. Thomas explains that to understand U.S. educational reform, foundational differences among the various groups or camps of reform need to be clarified. And, in a post he wrote this week, he has provided a map that we can use to help us understand educational reform.

He states that all reform is driven by ideology. He says:

and thus, those ideologies color what evidence is highlighted, how that evidence is interpreted, and what role evidence plays in claims public education has failed and arguments about which policies are needed for reform.

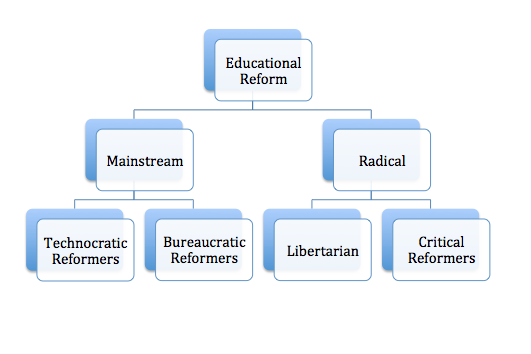

Education Reform Boxes and Categories

Dr. Thomas classifies reform into two categories, mainstream reform, and radical reform. Mainstream reform has been the dominant agent of change in U.S. education, with two “overlapping” reform divisions including technocratic and bureaucratic reformers. Thomas then creates two other divisions grouped as radical reforms, including libertarian and critical reformers. These reforms have been historically on the sidelines, but libertarians (who I’ve always considered as conservatives in disguise) have benefited from the movement to privatize education by both the bureaucratic and technocratic reformers.

Figure 1. Educational Reform Chart, according to P.L. Thomas. Education Reform based on P.J. Thomas . Education Reform Guide Retrieved November 15, 2013, from http://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com

Reform as a Continuum

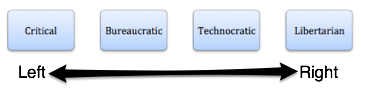

Thomas envisions the four categories at the bottom of Figure 1 as a continuum, moving from the left to the right as shown in Figure 2. I think it is important to note that Thomas suggest that those that claim that public education is failing do so with the full knowledge of their ideological foundation. For example, if the organization Achieve claims that American science education is failing, it needs to acknowledge its bureaucratic and technocratic philosophy is driving its public statements.

For those of us in science education, since 1957, the refrain has been: American science education is inferior to other nations, and that if science (and mathematics) is not upgraded, then the nation faces a reality of being at risk (A Nation at Risk, 1983). In the most recent rendition, even the prestigious National Research Council, which received funding from the Carnegie Institute, agreed with the authors of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), that K-12 science education is taught as a set of disjointed and isolated facts.

This can be debated. Most science teaching is organized around major topics, concepts or ideas. They are typically not taught in a disjointed fashion as the authors of the new standards claim. Look at any science textbook, and you will find that chapters are organized as unified units of content. But it was in the best interest of the dominant élite to make the claim that science (and mathematics) is contributing to America’s loss of competitive edge, that American students are lagging in achievement of students in other countries, and that the future workforce will be unable compete in the global marketplace. Standards in science or math are typically written and promoted by élite groups or committees of professionals, e.g. mathematic professors, linguists, or scientists. It’s not surprising that it was an élite group of scientists who wrote the science framework upon which the Next Generation Science Standards are based. But, this is not a new idea.

And don’t be fooled into thinking that the NGSS were written by classroom teachers. The framework was established by the élite committees appointed by the National Research Council. The science that makes its way into texts and that show up in standards are written by those who have the capital, and they typically go out of their way to defend it. Look carefully at the NGSS, and you find that the approach and the nature of the content, K-12, has not changed from the previous set of science standards which were published in 1996.

Figure 2. Ideological/Political Scale from Left to Right by P.L. Thomas. Education Reform Guide. Retrieved November 17, 2013, from http://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com

From Ideology to Reform Examples

In the framework presented here based on P.L. Thomas’ analysis of reform, the bureaucratic and technocratic ideologies of reform dominate the American education reform scene. There is overlap in these dominant ideologies, and billions of dollars have been invested and provided by private corporations, and the U.S. Department of Education. For example, $4.5 billion was awarded to 11 states and the District of Columbia to implement the federal Race to the Top (RT3) program.

The RT3 is the embodiment of the mainstream educational reform because of its bureaucratic and technocratic ideologies. Since 2008, the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation has invested more than $2 billion in educational reform, most of it to support the RT3’s program of college and career readiness. Follow this link to see a chart showing how the Gates Foundation spent it money on education. College and career readiness are the code words for standards-based and high stakes testing.

In Dr. Thomas’ continuum scale, the Common Core State Standards and the Next Generation Science Standards are examples of educational reform initiatives that overlap the bureaucratic and technocratic categories. These two sets of standards support the ideology that claims that American schools must make sure that students achieve at high levels of mastery, and that teachers implement a curriculum based on a common set of standards written by elites in the fields of mathematics, science and English/language arts. If you read the literature on the Achieve website you will find its ideology spelled out in statements such as these ( (Next Generation Science Standards. The Need for Science Standards. Retrieved November 17, 2013. http://www.nextgenscience.org):

- When we think science education, we tend to think preparation for careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, which are wellsprings of innovation in our economy.

- In 2012, 54% of high school graduates did not meet the college readiness benchmark levels in mathematics, and 69% of graduates failed to meet the readiness benchmark levels in science

- U.S. system of science and mathematics education is performing far below par and, if left unattended, will leave millions of young Americans unprepared to succeed in a global economy.

- To be competitive in the 21st century, American students must have the knowledge and skills to succeed in college and in the knowledge-based economy. Today, students are no longer just competing with their peers from other states but with students from across the globe.

- Many feel it is necessary for American students to be held to the same academic expectations as students in other countries. The successes of other nations can provide potential guidance for decision-making in the United States.

These statements provide some of the rationale for reform initiates that fundamentally focus on raising standards and increasing student achievement. Educational reform can be evaluated using “big” data systems that are based on high-stakes testing. Failures are highlighted quite easily by these reformers because they make unscientific statements about what constitutes success.

In Table 1, I’ve organized Dr. Thomas’ analysis into a chart identifying the sector and ideology of his reform categories. I’ve added another column that includes a few examples of the categories. These are my interpretations, and any criticism of my choices should be directed to me, not to Dr. Thomas.

Please note that many of the examples shown in the bureaucratic and technocratic sectors overlap, e.g Common Core, Next Generation Science Standards. I’ve also included a few historical events (Sputnik Hysteria), organizations (Achieve), and people (Paulo Freire) to provide additional examples of reform.

Table 1. Ideologies and Examples of Education Reform based on P.J. Thomas . Education Reform Guide Retrieved November 15, 2013, from http://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com (Examples are my own interpretations).

P.L. Thomas has provided an important tool for thinking about educational reform. As he said near the end of his article,

Regardless, then, of how accurate anyone believes this guide is, I would maintain that step one is to acknowledge that “educational reformer” is insufficient alone as an identifier and that ideology drives all claims of educational failure and calls for reform.

What reforms, events and people would you add to the examples posted in Table 1?

You must be logged in to post a comment.